Urinary Incontinence

What is urinary incontinence?

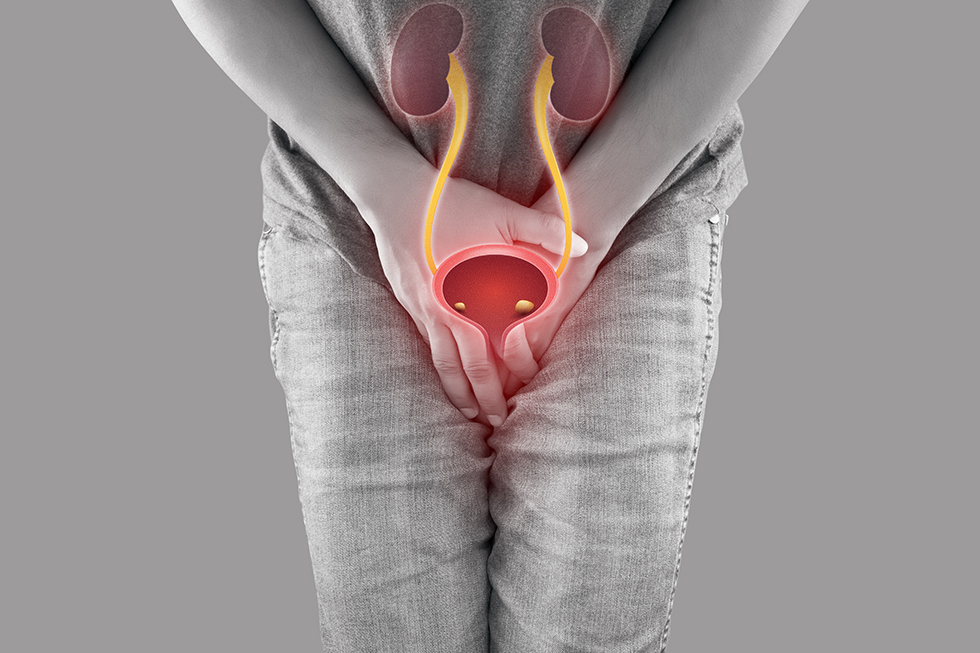

People with urinary incontinence have trouble controlling their bladder function and leak urine from the urethra.

The experience is of course unpleasant and affects a person’s daily life. People might feel embarrassed about their bladder control. They might plan activities around bathroom availability, nervous about having an “accident” when they’re out with friends or at work. They might try pads and other absorbent products, which can be uncomfortable and irritate the skin. And they might shy away from socializing, becoming isolated and depressed.

Fortunately, there are effective treatments for urinary incontinence.

Is urinary incontinence a normal part of aging?

Some people think urinary incontinence is just something to accept as they get older. But that’s not the case. It is possible to improve bladder control and reduce (or eliminate) leaks. Incontinence can be managed by making behavioral changes and doing exercises. There are also devices and surgical procedures that can help.

It’s worth talking to a health care professional about incontinence.

How does the urinary system work?

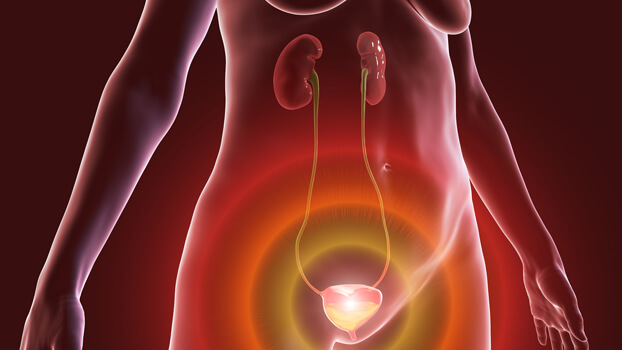

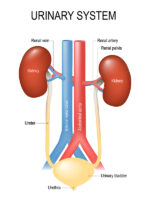

For most people, the urinary tract is made up of these key components:

- The kidneys are two fist-sized organs that filter blood and produce liquid waste (urine).

- The ureters are two tubes that connect the kidneys and the bladder. Urine flows from the kidneys, through the ureters, to the bladder. One ureter is connected to one kidney. Both ureters connect to the bladder on the other end.

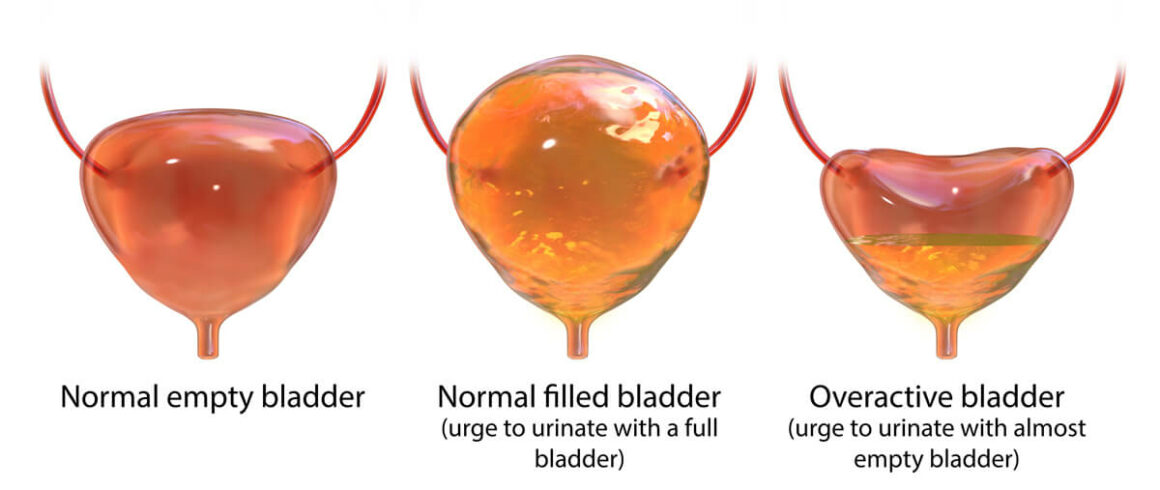

- The bladder is a flexible, muscular “holding tank” that stores urine until it’s time to empty it (“go to bathroom”). Usually, people start feeling the urge to urinate when the bladder is about half full.

- Sphincter muscles keep the bladder closed until it’s time to urinate.

- The urethra is the tube connecting the bladder and the outside of the body. When a person urinates, urine flows from the bladder to the toilet through the urethra.

- The pelvic floor is a group of muscles that support the pelvic organs. They are sometimes described as a “hammock” that keeps these organs in place.

When the bladder needs emptying, the brain signals for urination to start. Bladder muscles contract, which opens the sphincter muscles, allowing urine to flow from the bladder, through the urethra, and out of the body. When the bladder is empty, it relaxes again and the sphincter muscles close.

If a problem interferes with this process, urinary incontinence can occur.

What are the different types of urinary incontinence?

There are five main types:

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI)

This is the most common type. SUI occurs when there is sudden pressure on the bladder that makes the sphincter muscles open for a short time. A person might leak urine when they laugh, cough, sneeze, stand up, or lift heavy objects. Some people with SUI leak just a few drops of urine. But others might leak enough to need a change of clothes.

SUI is usually caused by damage to or weakening of the pelvic floor. This can happen after pregnancy, childbirth, pelvic surgery, and prostate surgery. Nerve injuries and a chronic cough may also contribute to SUI.

Urge urinary incontinence (UUI)

UUI occurs when the bladder muscles contract at the wrong time, even if there is no urine in the bladder. People with UUI feel an intense, sudden need to urinate and will leak urine if they can’t get to the bathroom in time. UUI is sometimes called overactive bladder (OAB).

UUI can be a symptom of several urological conditions, including bladder cancer, bladder stones, inflammation, and infections. It might also happen in people with neurological conditions, like multiple sclerosis, stroke, or spinal cord injury. Men with an enlarged prostate (e.g., BPH or prostatitis) can develop UUI, too.

Sometimes, no cause is found.

Mixed incontinence

People with mixed incontinence have symptoms of both SUI and UUI.

Overflow incontinence

With this type, the bladder reaches its capacity and cannot hold any more urine. Or people may be unable to empty their bladder completely. As a result, leaks occur. Urine flow may be slow or dribbling.

Overflow incontinence can happen if there is a blockage in the urethra or if the bladder muscles are weakened. It can also happen after pelvic surgery or with the use of certain medications. Unlike other types of incontinence, overflow incontinence is more common in men.

Functional incontinence

People with functional incontinence may have trouble recognizing that their bladder is full or be unable to reach the toilet in time. For example, a person with dementia or mental illness might not be aware that it’s time to urinate. Someone who uses a walker might not be able to access the path to the bathroom. And a person with arthritis might have difficulty unfastening buttons, buckles, or zippers on their clothing.

How is urinary incontinence different for men and women?

In general, women are about twice as likely to have incontinence than men are. Pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause can weaken pelvic floor muscles that support pelvic organs, including the bladder. In addition, women have shorter urethras than men do, so there is less muscle keeping urine contained in the bladder.

The anatomical differences between men and women also affect some of the causes and treatments of urinary incontinence. For example, a man might leak urine because of an enlarged prostate; a woman may do so after childbirth. For treatment, men may receive an artificial urinary sphincter, while women may use a vaginal pessary. (Read more about these devices below.)

Doctors use a combination of methods to determine what type of incontinence a person has

How is incontinence diagnosed?

Doctors use a combination of methods to determine what type of incontinence a person has. They will also consider whether related health conditions need to be addressed.

Medical history

Doctors usually start by asking questions about general health, urinary symptoms, and the effects of incontinence on daily life. Some example questions include the following:

- What, specifically, are your symptoms?

- How much urine do you leak?

- Do you have pain, discomfort, bloating, or similar symptoms?

- How long have you been having symptoms?

- What do you eat and drink regularly? Do you find that symptoms worsen after you’ve had a particular food or beverage?

- When do you typically eat and drink?

- What medications do you take (both prescription and over the counter)? How much and how often?

- Do you take dietary supplements? If so, what are they?

- Have you ever had pelvic surgery?

- Have your symptoms interfered with your daily life? How?

- How do these symptoms make you feel? Are you depressed or anxious?

- (For women) Have you given birth to children?

- (For women) Have you gone through menopause?

Urinary habits can be awkward to discuss, but it’s best to be open and honest about symptoms. Providing as much information as possible helps doctors come up with an effective treatment plan.

Bladder diary

A bladder diary is a record of how often a person urinates, how frequently they have leaks, and what they eat and drink each day. It also notes a person’s activities (such as coughing or laughing) when leaks occur.

Physical exam

The abdomen, genitals, rectum, and pelvic floor are examined. Women may have an internal pelvic exam. Men may have their prostate gland checked.

Pad test

This assessment involves wearing an absorbent pad for a certain period of time. The goal is to find out if the body leaks urine when it moves a specific way—and if so, how much?

A pad test can be done in two different ways:

- The patient wears a pad for an hour at the doctor’s office and does some activities, like exercise. At the end of the hour, the pad is weighed to see how much urine has leaked.

- The patient is given a set of pads to use at home for 24 hours. Used pads are stored in an airtight bag and weighed by the doctor at the end of the test. With this test, doctors can see how much urine leaks during a typical day and night.

Urinalysis

A urinalysis is a urine test. The doctor will check a urine sample for substances like bacteria or white blood cells (which might suggest an infection). Urine cytology is a test that checks for cancer cells in the urine.

Urine culture

Similar to a urinalysis, a urine culture also uses a urine sample. However, part of the sample will be placed in a petri dish in a lab for a few days. Lab technicians will check for bacteria or any other growth that could indicate an infection.

Urodynamic tests

Urodynamic tests assess the quantity of urine the body makes, how much the bladder can hold, the quality of the urine stream, and the rate at which urine flows. It also checks the strength of the sphincter muscles.

Imaging tests

With imaging tests, a doctor can see inside the urinary tract. These tests might include a bladder scan, X-ray, or ultrasound.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy allows a doctor to see inside the bladder using a special tool called a cystoscope. After a person is given local anesthesia, the doctor threads the cystoscope up the urethra and into the bladder. A camera at the end of the cystoscope provides an interior view.

Post-void residual urine test

This test measures how much urine remains in the bladder after a person urinates.

Treatment

How is incontinence treated?

There are effective treatments for urinary incontinence

Lifestyle changes

Often, the first steps toward better bladder control are lifestyle changes. These options can work well in combination with other treatments. They are also good ways to prevent incontinence from becoming a problem in the future:

- Quit smoking.

- Reduce fluid intake, especially at bedtime.

- Avoid foods and drinks that worsen symptoms. Alcohol, caffeine, spicy foods, and acidic foods are common bladder irritants.

- Lose weight if overweight.

- Make sure blood sugar is well-controlled.

- Take diuretic medication at times when a bathroom is close by.

Bladder retraining

The bladder can be “taught” to hold urine for longer periods of time. This technique starts with a urination schedule. For example, a person might decide to urinate every hour to start. They try to hold the urine for this hour, and when the time is up, they go to the bathroom. Once their body is used to this schedule, they increase the time by 15 minutes. Then 30 minutes. Eventually, they may train their bladder to hold urine for 3 to 4 hours between bathroom visits.

This technique takes time and practice. A person shouldn’t feel discouraged if they can’t increase the time by 15 minutes. Trying a shorter time frame, such as five minutes, is a good goal, too.

Double voiding

Double voiding means urinating twice in one bathroom trip and trying to empty the bladder. This technique can be helpful for people with overflow incontinence.

Medications

There are medications available that can relax the bladder. Here are some examples:

- Anticholinergics (such as oxybutynin and tolterodine). These drugs improve the neurological connection between the brain and the bladder so messages can transmit properly.

- Beta agonists (such as mirabegron). These drugs relax bladder muscles and increase the amount of urine the bladder can store.

- Alpha blockers (such as alfuzosin and tamsulosin). An enlarged prostate can cause urinary symptoms, including incontinence, in men. Alpha blockers treat those symptoms by relaxing prostate muscle fibers and bladder neck muscles.

- Topical estrogen. The decline of estrogen at menopause can weaken the urethra and tissues around the bladder. Estrogen may strengthen these areas.

Botox injections are another possibility. Like the medications noted above, Botox injections can relax the bladder and allow it to hold more urine. Injections are delivered through a cystoscope—a hollow tube that is gently placed into the urethra. (Local anesthesia may be given.) The effects of Botox injections do wear off over time, and some people need to repeat treatment every 3 to 12 months.

Doctors may also prescribe drugs used to treat underlying conditions, such as an enlarged prostate or urinary tract infection.

Note: Currently, the FDA has not approved any medications to treat stress urinary incontinence.

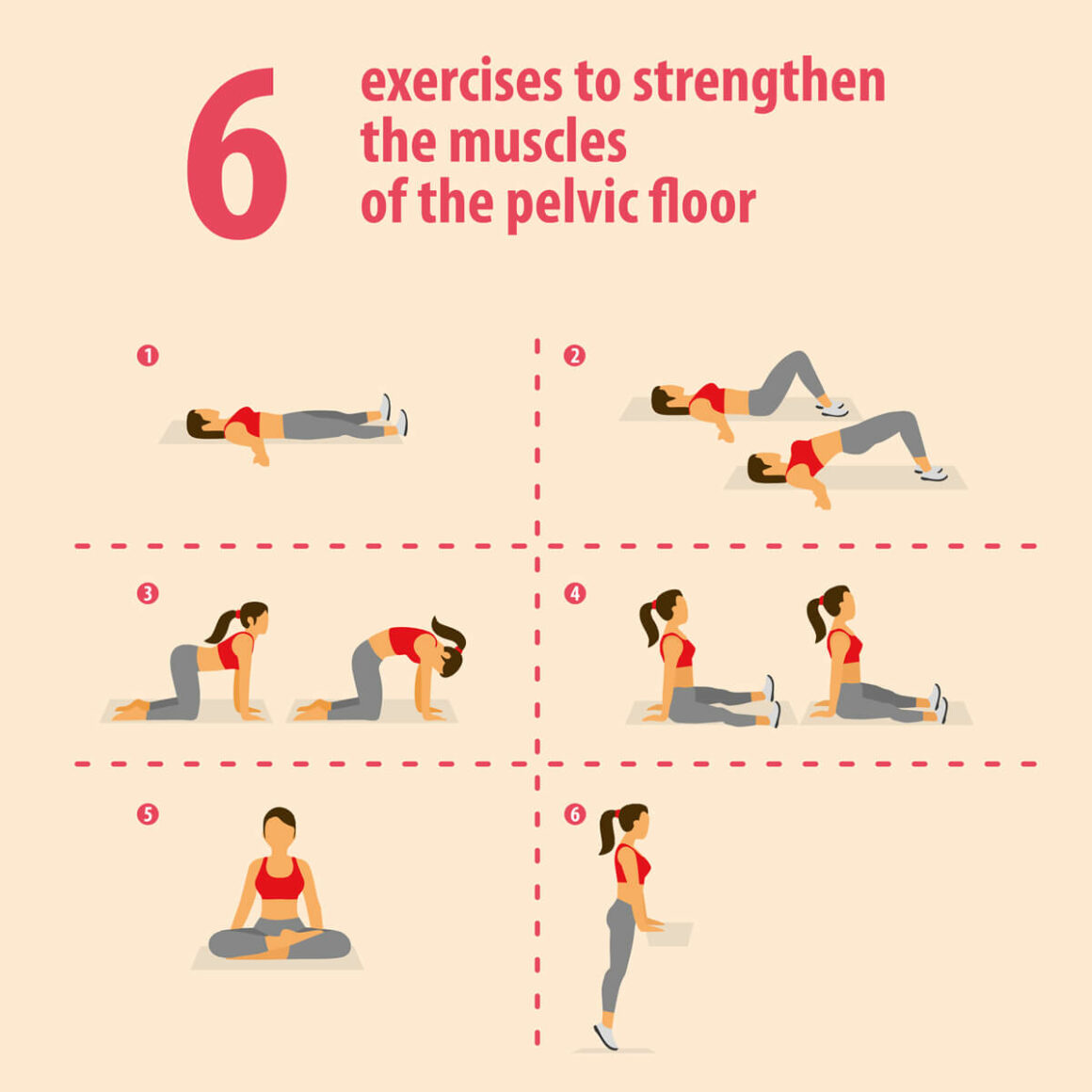

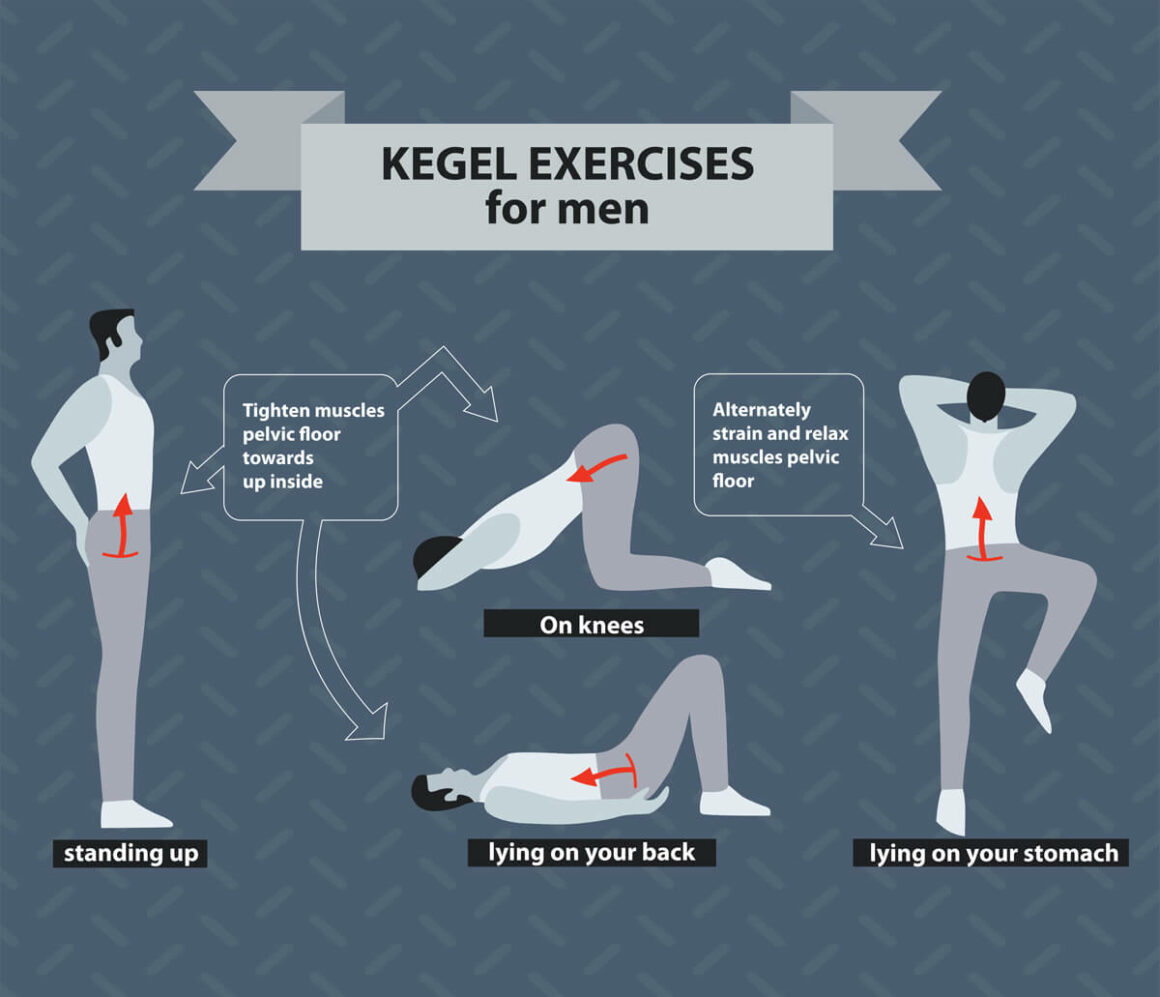

Pelvic floor muscle training

At the gym, people do lunges to strengthen their hamstrings or pushups to tone their upper body. The same principle applies to the pelvic floor muscles. Exercising this area can support the muscles that control urine flow.

Sometimes, this approach is called pelvic floor physical therapy. Specialists help patients identify the correct muscles and teach specific exercises, such as Kegel exercises.

Pelvic floor muscle training might also include the following methods:

- Biofeedback. This technique, done by a specialist, uses a sensor (placed in the vagina or anus) to help patients find and control their pelvic floor muscles. When they squeeze these muscles, they can see their movements graphed on a monitor.

- Electrical stimulation. A physical therapist delivers a mild electrical current to the pelvic floor area through a probe in the vagina or anus. The current contracts bladder muscles.

- Vaginal cones. Women place a weighted cone in the vagina and squeeze the pelvic floor muscles to keep it in place. This technique can be done at home.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

Located at the lower end of the spine, the sacral nerves help transmit sensory messages that are important for good bladder and pelvic floor function. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) applies gentle electrical pulses to these nerves by way of the tibial nerve, which is found in the leg. To access it, a doctor places a small needle electrode in the ankle. The electrical pulses then move up the tibial nerve to the sacral nerves. There might be a tingling sensation, but the process shouldn’t hurt.

People undergoing PTNS may need several treatments before they start seeing results. Some patients have additional treatments every once in a while to maintain improvements.

Sacral nerve stimulation

This approach uses a special device that is surgically implanted in the belly. The device sends a mild electrical current to the sacral nerves, which play a role in bladder function. A person can manage the current with a hand-held controller.

Vaginal pessaries (for women)

A vaginal pessary is a flexible device that a woman inserts into her vagina. It reduces leaks by putting pressure on the vaginal wall, which helps support the bladder and urethra. Pessaries are available by prescription and over the counter. If a pessary is fitted well, it shouldn’t be uncomfortable.

A prescription pessary is custom fitted, and it’s important to follow a doctor’s directions on its care. Women might be able to remove, clean, and reinsert the pessary themselves. In other cases, they’ll have the pessary removed, cleaned, and replaced at the doctor’s office.

A doctor will also advise on how long to wear the pessary at one time. Often, women wear their pessary during the day and remove it at night. Wearing it for too long might lead to irritation. Pessaries might be removed before intercourse as well.

Over-the-counter pessaries are disposable, intended for just one use. Inserted with an applicator, they can be used for up to 8 hours and removed by pulling a string that’s attached.

Penile clamp/clip (for men)

Men with incontinence may choose to try a penile clamp or clip. These devices are worn on the penis and reduce urine leaks by placing pressure on the urethra.

The clamp is worn only during the day, not during sleep. It also needs to be removed every 1 to 2 hours so that urine can be released. Each time the clamp is put back on, it should be in a different spot from the time before. Avoid setting the clamp too tight.

A doctor will recommend what type of device to use.

Urethral injections

With this approach, a doctor injects a synthetic bulking agent into the urethra. This method helps the sphincter close more effectively.

Urethral injections can be administered at the doctor’s office under local anesthesia. Eventually, the injected material is absorbed by the body, so additional injections may be necessary.

Urethral sling

A urethral sling is a strap of material that is surgically implanted to support the urethra. Slings may be made from tissue from a patient’s own body or from synthetic material (mesh). They can be implanted in several ways.

In women, the sling may be implanted through an incision in the vagina or urethra. In men, the sling is usually placed between the scrotum and rectum.

Bladder neck suspension (for women)

Women may opt for bladder neck suspension surgery. With this technique, sutures starting in the vagina are attached to ligaments near the pubic bone. In this way, the urethra and sphincter muscles are supported and less likely to open by accident.

Patients undergoing bladder neck suspension may be given general anesthesia. The surgery may be open (using an abdominal incision to reach the area) or laparoscopic (using a smaller incision, specially designed instruments, a camera, and a video monitor).

Other terms for this procedure include retropubic suspension, colposuspension, and Burch suspension.

Artificial sphincter (for men)

An artificial sphincter system is a 3-part device that is surgically implanted. The system includes an inflatable cuff (which wraps around the urethra), a balloon reservoir (placed in the belly), and an activation pump (placed in the scrotum).

The cuff acts as the sphincter itself. Normally, it is filled with fluid. This arrangement keeps the urethra closed so urine won’t leak out.

When a man needs to urinate, he presses the pump in his scrotum. Then, the fluid flows out of the cuff into the balloon reservoir, which holds the fluid temporarily. At this point, the urethra opens, and urine can flow out.

Once he’s finished urinating, the man presses the pump again. The fluid flows from the reservoir back to the cuff, closing the urethra once again.

Catheterization

In rare cases, people with overflow incontinence might need to use a catheter—a flexible tube that drains urine from the bladder into the toilet or into a collection bag. There are several type of catheters. Some are permanent, but others can be inserted and removed as needed by the patient or a caregiver at home.

Surgery to remove blockage

If incontinence is caused by an obstruction, surgery can be done to clear the pathway. For example, men with an enlarged prostate might have excess prostate tissue removed, relieving pressure on the urethra. This makes it easier for urine to flow out.

Augmentation cystoplasty (bladder enlargement)

This procedure makes the bladder larger, so it can hold more urine. People who undergo augmentation cystoplasty might still be unable to completely empty their bladder. They may need to use a catheter for the long term.

Resources

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

“FAQs: Urinary Incontinence”

(Last reviewed: July 2020)

https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/urinary-incontinence

American Urogynecologic Society

“Botox® Injections to Improve Bladder Control”

(2018)

https://www.voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Botox.pdf

American Urological Association

Jaspreet S. Sandhu, MD, et al.

“Incontinence after Prostate Treatment: AUA/SUFU Guideline (2019)”

(2019)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/incontinence-after-prostate-treatment#x14371

Kobashi, Kathleen C., MD, FACS, FPMRS, et al.

“Surgical Treatment of Female Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI): AUA/SUFU Guideline (2017)”

(2017)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/stress-urinary-incontinence-(sui)-guideline#x4496

Winters, J. Christian, et al.

“Adult Urodynamics: AUA/SUFU Guideline (2012)”

(2012)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/urodynamics-guideline

Cleveland Clinic

“Augmentation Cystoplasty (Bladder Augmentation)”

(Last reviewed: June 1, 2015)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/15846-augmentation-cystoplasty-bladder-augmentation

“Overflow Incontinence”

(Last reviewed: November 5, 2021)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22162-overflow-incontinence

Healthline.com

Ross-Hazel, Lindsay and Kristeen Cherney

“Overflow Incontinence: What Is It and How Is It Treated?”

(Updated: August 12, 2020)

https://www.healthline.com/health/overactive-bladder/overflow-incontinence

Scaccia, Annamarya

“Is it Possible to Have a Loose Vagina?”

(Updated: May 11, 2022)

https://www.healthline.com/health/womens-health/loose-vagina

International Urogynecological Association

“Colposuspension for Stress Incontinence”

https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/conditions/colposuspension-for-stress-incontinence/

Mayo Clinic

“Bladder control: Medications for urinary problems”

(July 15, 2022)

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/urinary-incontinence/in-depth/bladder-control-problems/art-20044220

“Urinary incontinence: Diagnosis and treatment”

(December 17, 2021)

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/urinary-incontinence/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20352814

MedlinePlus.gov

“Urge incontinence”

(Review date: July 31, 2019)

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001270.htm

“Urinary incontinence – urethral sling procedures”

(Review date: January 10, 2021)

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007376.htm

Medscape.com

Vasavada, Sandip P., MD

“What is overflow urinary incontinence?”

(Updated: January 22, 2021)

https://www.medscape.com/answers/452289-172411/what-is-overflow-urinary-incontinence

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

“How to Use Your Incontinence Clamp”

(Last updated: February 7, 2022)

https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/incontinence-clamp

National Association for Continence

“Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Procedures”

https://www.nafc.org/female-stress-incontinence-procedures

“Incontinence Conditions From A – Z”

https://www.nafc.org/conditions-overview

“Injection Therapy for Incontinence”

https://nafc.squarespace.com/injection-therapy

Neurology and Urodynamics

Krhut, Jan, et al.

“Pad weight testing in the evaluation of urinary incontinence”

(First published: June 24, 2013)

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/nau.22436

Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

“Urinary incontinence”

(Page last updated: January 31, 2019)

https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/urinary-incontinence

The Simon Foundation for Continence

“Functional incontinence”

https://simonfoundation.org/functional-incontinence/

“Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation (PTNS)”

https://simonfoundation.org/ptns/

“Sacral Nerve Stimulation for Incontinence”

https://simonfoundation.org/sacral-nerve-stimulation/

UpToDate.com

Clemens, J. Quentin, MD, FACS, MSCI

“Urinary incontinence in men”

(Topic last updated: January 3, 2022)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urinary-incontinence-in-men

Doctors and editors at UpToDate

“Patient education: Surgery to treat stress urinary incontinence in women (The Basics)”

(Retrieved: April 4, 2022)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/surgery-to-treat-stress-urinary-incontinence-in-women-the-basics

Doctors and editors at UpToDate

“Patient education: Urinary incontinence in males (The Basics)”

(Retrieved: February 26, 2022)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urinary-incontinence-in-males-the-basics

Lukacz, Emily S., MD, MAS

“Patient education: Urinary incontinence in women (Beyond the Basics)”

(Topic last updated: January 21, 2022)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/urinary-incontinence-in-women-beyond-the-basics

Urology Care Foundation

“Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI)”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/s/stress-urinary-incontinence-(sui)

“Urodynamic Tests: What You Should Know”

(2020)

https://www.urologyhealth.org/educational-resources/urodynamic-tests

“What is Cystoscopy?”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/c/cystoscopy

“What is Urine Cytology?”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/u/urine-cystology

Uroweb.org (European Association of Urology)

“Sling implantation in men”

(Last updated: April 2022)

https://patients.uroweb.org/treatments/sling-implantation-men/

WebMD

Brown, Steven

“What Is a Post-Void Residual Urine Test?”

(February 10, 2022)

https://www.webmd.com/urinary-incontinence-oab/post-void-residual-test